Exploring Legal and Policy Responses to Opioids: America’s Worst Public Health Emergency

By

By

James G. Hodge, Jr., J.D., LL.M.[1]*

Chelsea L. Gulinson, J.D.[2]**

Leila F. S. Barraza, J.D., M.P.H.[3]***

Walter G. Johnson, M.S.T.P.[4]****

Drew Hensley[5]******

Haley R. Augur[6]******

On October 26, 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) formally declared a national state of public health emergency (PHE) in response to the opioid epidemic.[7] Urged by the White House’s Opioid Commission,[8] HHS’s declaration, since renewed multiple times,[9] assimilates emergency declarations among a handful of state, tribal, and local governments.[10] Countless public and private sector entities have engaged in additional opioid emergency response efforts across the United States.

These emergency declarations and measures collectively respond to the worst PHE confronting the country since the origination of this specific emergency classification in 2001.[11] Americans across all socioeconomic groups are at risk of, or already addicted to, opioids in one form or another.[12] Several hundred thousand Americans have lost their lives to prescription or illicit opioid misuse over the course of this epidemic.[13] Nearly 130 more Americans die each day from opioid misuse.[14] Millions are directly impacted by excess morbidity arising from opioid use disorders (OUDs).[15] Most people know someone who is at risk of, or has succumbed to, opioid abuse.[16] This epidemic is truly the juggernaut of PHEs.[17]

While emergency responses to date are purposeful and often well-intentioned, for manifold reasons they have also proven inadequate in authorizing and funding sufficient, efficacious responses.[18] In many ways, the unique qualities of opioids as a class of drugs defy traditional public health and law enforcement interventions. At one end of the spectrum, prescription opioids like OxyContin®[19] have revolutionized the treatment of chronic pain as the “fifth vital sign.”[20] Over the years, massive distributions of these drugs[21] has led to extensive, long-term addictions among millions of Americans. As a result, substantial prescription limitations are now in place[22] and major litigation against opioid manufacturers and others is ongoing.[23] At the other end, highly addictive illicit opioids like carfentanyl[24]—arriving through the mail or across our borders—have instantly killed tens of thousands of users lacking rapid access to naloxone[25] or other medical interventions.[26]

Adding to the complexity is the interconnection of these two ends.[27] Temporary access to prescription opioids for many patients is a gateway to illicit opioid use. Up to eighty percent of heroin users first got hooked on prescription opioids.[28] Unsurprisingly, regulating this diverse class of drugs is legally convoluted. Simple solutions like total bans of prescription opioids for all patients are non-viable given their accepted role and efficacy in treating pain.[29] Vilifying illicit opioids users (akin to “crack addicts” historically subjected to heavy-handed law enforcement) is grossly unfair and serves no legitimate public health purpose.[30] Curtailing access to illicit opioids is formidable given the free flow of these drugs.[31] Substituting other drugs in place of opioids, like marijuana, carries its own legal baggage and repercussions.[32] Developing new and non-addictive palliative drugs is promising, but likely years away. Rescinding the national PHE declaration only admits defeat.

While major legal and policy strides have been undertaken to curb the opioid epidemic,[33] more significant approaches and greater investments are needed to prevent excess mortality and morbidity.[34] Commencing with an assessment of the impacts of the opioid crisis, existing legal and policy responses, and related failures are explained. A series of interventions are proposed to (1) stymie opioid-related overdoses and deaths in real time and (2) obviate deleterious impacts for future generations.

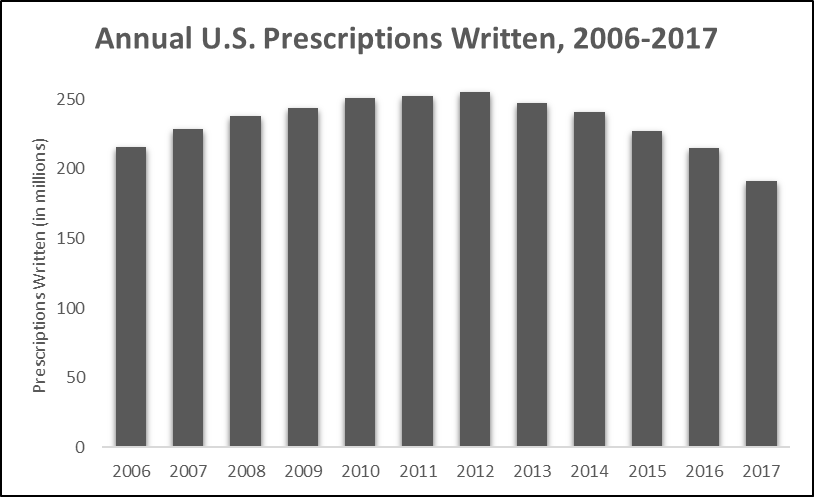

The evolving American opioid epidemic began with a shift in how health care providers treat pain.[35] Long-standing, widespread inattention to palliative care among millions of patients heightened ethical arguments and altered physician attitudes over prescribing narcotic pain medications in the 1990s.[36] Experts[37] and advocates[38] pushed for more lenient medical board oversight and expanded the prescribing of lawful narcotics to treat pain. In 1996, Purdue Pharma® released its opioid-based pain reliever, OxyContin®, allegedly assuring medical practitioners that it was non-addictive.[39] By 2000, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Joint Commission were promoting palliative care assessments for many patients.[40] The national push to treat pain was fueled by massive allocations of opioids. From 1997 to 2007, opioid prescriptions steadily rose seven-hundred percent (see Figure 1),[41] cresting in 2012 when nearly 260 million opioid prescriptions were written.[42]

Figure 1. U.S. Opioid Prescriptions in Millions (2006–2017)[43]

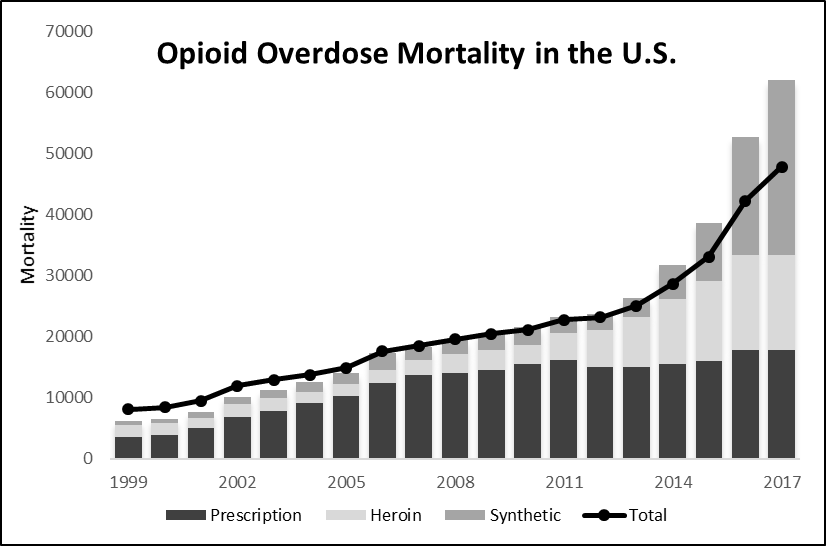

As prescription rates rose so did opioid overdose-related mortality.[44] Its addictive qualities entice patients to continuously ramp up their doses to dangerous levels. In most fatal overdoses, respiratory depression results in oxygen starvation that is sometimes coupled with cardiac arrest or arrhythmia and excess fluid in the lungs.[45] Overdose deaths increased by nearly six-hundred percent from 1999 to 2017 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Opioid Overdose Mortality (1999–2017)[46]

To date, opioids have caused nearly 400,000 confirmed American deaths; yet actual numbers may be considerably higher.[47] While abuses of prescription opioids were at the source of many of these deaths initially, illicit drugs (e.g., heroin) and synthetic opioids[48] (e.g., fentanyl) became primary causes of deaths in 2010 and 2013, respectively.[49] By 2016, American fatalities stemming from synthetic opioids exceeded those due to prescription opioids.[50] Absent greater interventions, one estimate suggests approximately 500,000 more deaths may occur between 2017 and 2027.[51]

Additional negative impacts underlie multiple classes of opioids.[52] Neonatal abstinence syndrome, affecting newborns exposed to opioids in utero, nearly tripled from the late 1990s to the early 2010s.[53] Almost 22,000 newborns were diagnosed in 2012 alone.[54] From 2001 to 2011, the number of patients admitted for OUD treatments at publicly-funded entities increased by 348%.[55] In 2016, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) estimated that nearly twelve million individuals misused opioids and 2.1 million persons had an actual disorder.[56] Recent findings suggest that OUDs occur in eight to twelve percent of patients taking opioids therapeutically;[57] consequently, hundreds of thousands of Americans are at heightened risk of opioid abuse.[58]

Escalations of OUDs and related mortality are especially alarming when compared to similar data concerning other harmful substances like tobacco or alcohol. Opioids essentially cause death faster—and among a greater proportion of persons using them—than most other substances. While regular tobacco use can reduce total life expectancy by ten years,[59] opioid overdoses lead to sudden early loss of life in younger individuals.[60] One estimate suggests that twenty percent of all deaths of Americans aged twenty-five to thirty-four in 2016 involved opioid misuse.[61] In contrast, tobacco use only minimally impacts survival rates for adults under age thirty five.[62]

Excessive alcohol consumption and related injuries cause around 88,000 fatalities per year,[63] which actually exceeds reported opioid-related mortality. However, alcohol-related deaths arise from a considerably larger pool of prospective at-risk users. Nearly sixty-seven million persons in the United States reported monthly binge drinking in 2017.[64] Even if alcohol deaths were attributable solely to these users, still only about .001% of them die each year. By comparison, in 2017, overdose deaths (48,000) are 3.32 times more likely among the estimated eleven million Americans misusing opioids in 2017.[65]

Public health impacts of opioid-related abuses also far outweigh morbidity and mortality data related to infectious disease outbreaks or natural disasters resulting in national or regional PHEs. The H1N1 outbreak claimed only 12,500 lives between 2009 and 2010,[66] which is actually considerably fewer than many annual flu seasons in the United States.[67] Emerging infectious conditions, like Ebola virus disease[68] and Zika virus,[69] caused a mere handful of known deaths in the U.S. (although populations in other countries lacking public health resources were ravaged). Natural disasters, like Hurricanes Katrina (2005),[70] Maria (2017),[71] and Michael (2018),[72] have collectively caused several thousand instant or near-time fatalities. Still, the totality of deaths related to all of these PHEs (and many others) nationally over the last 20 years do not come close to the sheer numbers of deaths related to opioids.

Emergency public health powers and interventions in response to other PHEs, including disasters and infectious disease outbreaks, have helped to quell morbidity and mortality.[73] Consequently, effective legal and policy responses to the opioid crisis may greatly improve public health outcomes.[74] Public and private sector entities and actors are actively engaged in various legal response efforts to stymie opioid-related impacts supported by declared emergencies and other legal interventions. However, these responses comprise a patchwork of uncoordinated and sometimes specious efforts that collectively fail to sufficiently suppress opioid-related mortality and morbidity nationally.

Federal responses to the opioid crisis tend to center on large scale efforts and funding, leaving frontline responses up to state, tribal, and local governments. HHS’s declaration of a national PHE in October 2017 raised national awareness and stimulated a series of key interventions.[75] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tightened its opioid prescribing guidelines.[76] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) required increased communication between pharmacies and opioid prescribers.[77]

On March 23, 2018, President Trump signed legislation[78] allocating $2.3 billion for federally-based efforts, such as CDC’s prescription monitoring activities,[79] opioid research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and response efforts at the VA, Department of Justice (DOJ)[80] and Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[81] An additional $1 billion was set aside for state grants funded through SAMHSA.[82] Additional federal assistance has focused on helping children of opioid misusers and promoting anti-addiction efforts in rural and underserved areas.[83] On October 24, 2018, President Trump signed the bipartisan SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act),[84] which aims to curb drug imports, increase access to addiction treatments, and promote development of new non-addictive pain relievers.

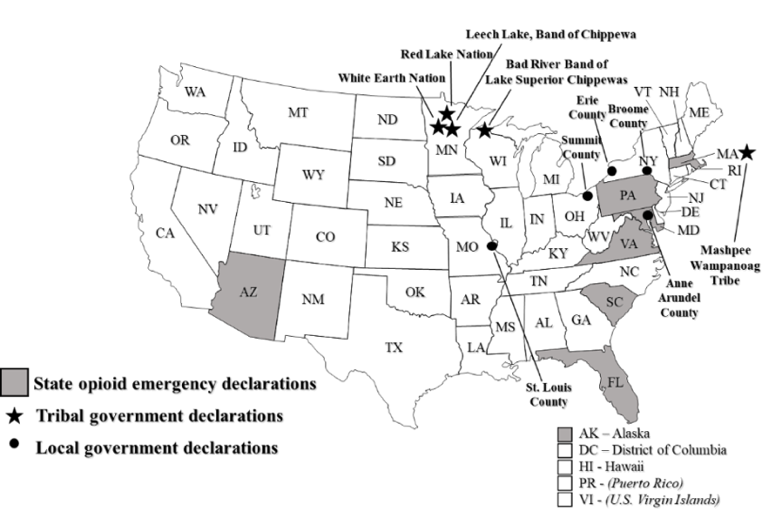

As per Figure 3, eight states and multiple tribal and local governments have declared their own opioid-related emergencies.[85] Tribal authorities, including the White Earth Nation and the Leech Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, were the first jurisdictions to declare opioid-related emergencies in 2011.[86] Massachusetts was the first state to declare an emergency in 2014.[87] States like Arizona and South Carolina have classified their epidemic as public health emergencies.[88] Other states, like Alaska and Pennsylvania, have legally declared states of disaster.[89] Local public health and law enforcement officials in Snohomish County, Washington are responding to its opioid crisis as if it were a natural disaster.[90]

Figure 3. Subnational Opioid-Related Emergency Declarations[91]

Collectively, these legal declarations supplement an array of existing public health law and policies to limit the flow of opioids through (1) enhanced prescription monitoring, (2) coordinated public communications, and (3) increased funding for efficacious medically-assisted treatment (MAT) and other preventive measures.[92] Multiple states allow first responders to carry and distribute naloxone via their emergency declarations (Arizona, Alaska, Massachusetts, Florida, and Pennsylvania).[93] Standing orders provide an effective route to save lives in real time by authorizing pharmacists to dispense naloxone to law enforcement officials and others without a prescription.[94]

Uptake and implementation of Good Samaritan Acts (GSAs) increase access to medical aid for overdosers.[95] Under these laws, bystanders seeking assistance for individuals experiencing opioid overdoses are protected from criminal prosecution for possession of a controlled substance or drug paraphernalia.[96] While their efficacy is not fully proven, researchers in a 2011 study found that opiate users were eighty-eight percent more likely to call 9-1-1 during an overdose if they were knowledgeable of GSA protections.[97]

States are also increasing the tracking and limitation of opioid prescriptions. Developed initially over a century ago to combat abuses of then-legal heroin and cocaine,[98] prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) comprise of electronic databases allowing health care providers to (1) better track whether a patient has received a controlled substance from other providers and (2) the patient’s daily prescribed dosage.[99] All states utilize PDMPs, but at least three states (Arizona, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania)[100] employ enhanced surveillance through their emergency declarations.[101] As of April 2018, twenty-eight states have also implemented laws restricting the number of days or dosage of opioids that a patient may receive,[102] with exceptions for those most in need of palliative care. South Carolina has legislatively restricted opioid prescribing to minors and required licensing among addiction counselors.[103]

Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly being held accountable for their roles underlying the crisis. From January to September 2018, national prescription opiate litigation reportedly jumped from 229 to 1,250 pending actions.[104] Among these cases, twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia have sued Purdue Pharma® for “deceptively marketing” OxyContin®.[105] In response, Purdue “restructured and significantly reduced [its] commercial operation and will no longer [promote] opioids to prescribers.”[106] Liability claims have also been brought against other drug companies, distributors, retailers, rehabilitation centers,[107] and the Joint Commission.[108] In August 2018, President Trump asked then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions to file a separate federal lawsuit against opioid manufacturers.[109]

Federal authorities have also cracked down on unscrupulous opioid prescribing and distribution. In 2017, the DOJ tripled its prosecutions for distributing illicit fentanyl,[110] including indictments against foreign manufacturers and distributors.[111] In April 2018, federal agents arrested a couple behind the largest dark web fentanyl conspiracy in the United States.[112] Later that same year, then-Attorney General Sessions announced charges against two Chinese citizens for “operating a conspiracy that manufactured and shipped deadly fentanyl analogues” to the U.S., causing at least two overdose-related deaths.[113] In June 2018, the DOJ publicly announced charges against hundreds of health care providers for fraudulent opioid prescriptions.[114]

When HHS’s Secretary Alex Azar announced on October 23, 2018, that opioid overdose deaths may have begun to “plateau,” he conceded that the nation is still “far from the end of the epidemic.”[115] In reality, the crisis may merely be shifting gears. Opioid overdose deaths from prescription opioids are declining in some places,[116] but deaths from illicit opioids are rising elsewhere.[117] Federal authorities have been criticized for failing to act swiftly and fully in exerting the gamut of their emergency powers and efforts.[118] In October 2018, the General Accounting Office reported that the federal government has not utilized the dozen legal powers or authorities to respond under its PHE declaration.[119] Though urged by his own White House Commission, President Trump has never declared an additional national state of emergency to supplement HHS’s PHE and free up millions more in response dollars.[120]

While the epidemic raged on, initial Congressional legislative proposals languished for months, lacked sufficient funds,[121] denied increased access to life-saving medications,[122] and ignored multiple recommendations of the White House Commission.[123] Aware of China’s role in fueling the opioid crisis based on an international report released in early 2017,[124] Congress initially did little to address the importation of toxic synthetic opioids, often laced with other illicit drugs.[125] For months opioid packages from Chinese laboratories went largely undetected through the United States Postal Service (USPS) due in part to a lack of advanced technology.[126] The afore-mentioned federal SUPPORT Act finally requires USPS to share electronic data with Customs and Border Protection on “at least 70 percent of international mail.”[127]

Many have called for greater public health legal efforts coordinated by states and localities across the frontlines of the epidemic.[128] Every state is negatively impacted in varying degrees,[129] but only eight have declared opioid-related emergencies (see Figure 3),[130] authorizing a divergent series of emergency responses (see Figure 4).[131] Other states aspire to do more but face funding shortages or legal limitations. West Virginia suffers the highest opioid-related death rate per capita nationally but received no additional federal funding from HHS’s original PHE declaration.[132] Consequently, like many states, it developed its own PHE response plan[133] in lieu of declaring a state of emergency.

Figure 4. State Opioid Emergency Declaration Legal Responses[134]

| Responses | MA | VA | AK | MD | FL | AZ | SC | PA |

| Naloxone Standing Order | X | X | X | X | ||||

| First Responders Carry/Distribute Naloxone | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Enhanced PDMP Surveillance | X | X | X | |||||

| Opioid Prescribing Restrictions | X | X | ||||||

| Increased Funding for Treatment | X | X | ||||||

| Interagency Coordination | X | X | X | X |

States not declaring PHEs have implemented a scattered series of harm reduction measures instead.[135] Stigmas surrounding opioid addiction curtail some effective measures including syringe services programs (SSPs).[136] Supported by the federal Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 and HHS guidance, SSPs help prevent the spread of blood-borne infections by offering clean needles and used needle disposal along with prevention and education materials.[137] Despite their efficacy,[138] many states are slow to implement SSPs,[139] fail to legalize them,[140] or rescind support.[141] As a result, access to clean needles varies extensively across the United States.[142]

Other legal responses to the epidemic are antiquated or off-target, assimilating failed efforts from the regrettable “War on Drugs” campaign in the 1980s.[143] In 2014, Tennessee authorized prosecution of pregnant women with assault for the illegal use of narcotics.[144] In 2017, an Ohio municipality proposed a “three strikes and you’re dead” law that would allow emergency medical providers to refuse to dispatch antidotes to multiple “repeat” overdose victims.[145] On August 23, 2018, President Trump suggested imposing the death penalty for fentanyl dealers.[146]

Some legal approaches run counter to modern techniques to curb opioid-related deaths. Quitting opioids “cold turkey” is unsafe and often ineffective.[147] Medicated assisted treatment (MAT) is considerably more efficacious, but many recovery centers have not adopted it[148] due in part to legal prescribing impediments.[149] Supervised injection facilities (SIFs) offering protected havens for drug users are globally proven to reduce overdose deaths.[150] However, United States Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein opined in August 2018 that SIFs are unlawful, promising “swift and aggressive [DOJ] action” against their known operation.[151]

Some responses may prove misguided. The FDA recently approved DSUVIA,[152] a new, sublingual (under-the-tongue) opioid more potent than fentanyl,[153] developed with support from the United States Department of Defense.[154] While the drug can only be dispersed in health care settings, former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb expressed concerns over the risk of diversion.[155] Even within controlled health care uses, DSUVIA’s potency may exacerbate potential patient abuse.[156]

Conflicts of interest have also plagued response efforts. Multiple United States Senators have received campaign funding from pro-opioid interest groups.[157] Owners of Purdue Pharma® not only sell OxyContin® but also its generic equivalents.[158] When FDA entrusted pharmaceutical companies and drug distributors to help manage opioid safety programs, it essentially allowed “the fox [to guard] the henhouse.”[159] Drug distributor McKesson®,[160] for example, was entrusted to run its own “risk evaluation and mitigation strategy” safety program[161] overseeing potential misuses of transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl.[162]

Existing limits in reigning in the opioid crisis via emergency or other public health legal powers[163] have not only failed to curb the epidemic but may be essentially fueling it. More aggressive and expansive approaches are needed to reduce real-time morbidity and mortality. Innovations under consideration or in early phases of implementation nationally or regionally have strong potential for positive impacts. In 2018, for example, multiple digital platforms broadcasted opioid prevention messages, including the White House’s “The Truth About Opioids” campaign importing voice-controlled artificial intelligence devices to respond to opioid-related inquiries.[164] To address worker productivity losses,[165] the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation developed a pilot program for employers to better understand employees’ addiction and recovery facets.[166]

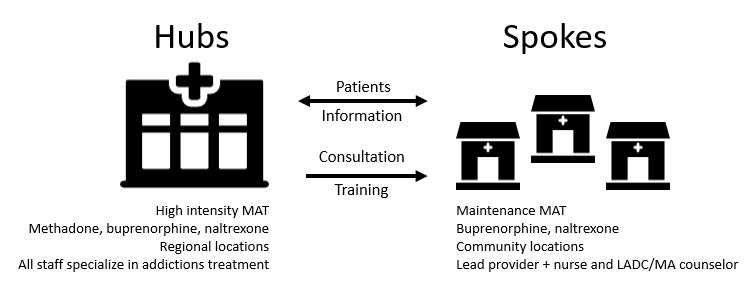

Innovative training, testing, treatment, and notification options for at-risk persons or their providers are emerging.[167] Boston University is integrating addiction training into its medical school curriculum, providing a national model for other programs.[168] Government-sponsored communications in New York and other jurisdictions notify physicians when one of their patients dies by overdosing on opioids they prescribed. These efforts have led to a nearly ten-percent reduction in physician prescribing practices.[169] Drug checking services[170] offer fentanyl testing strips to help ascertain dangerous drugs prior to their use.[171] Some health insurance companies will stop covering OxyContin® in 2019.[172] Huntington, West Virginia employs mental health professionals within its emergency response departments.[173] Vermont integrates a successful hub-and-spoke system for expanding OUD treatment (see Figure 5).[174]

Figure 5. Vermont Hub & Spoke System[175]

More progressive responses may reduce opioid-related mortality and morbidity over the short- and long-terms. Some common-sense approaches entail minimal expenditures to execute. Public health authorities may recommend that patients store their prescription opioids (like guns) in secure containers at home to deter nonintentional or intentional misuse by others. Any health care provider treating patients for pain should (1) implement more substantial informed consent processes (e.g., mandatory videos, risk/benefit information) designed to effectively communicate potential harms and (2) closely look for signs of addiction among at-risk patients.

Other efforts require greater funding commitments nationally. Reaching patients in rural settings, where per capita death rates can exceed urban areas, may be facilitated through student loan forgiveness mechanisms for health care providers practicing in these settings, whether directly or remotely via telemedicine.[176] National models for greater oversight and regulation of drug rehabilitation centers could deter devious practices subjecting patients to cyclical misuse. Prisoners, often at heightened risk of opioid misuse, need access to enhanced mental health and substance abuse treatment options while incarcerated and social work assistance to avoid opioid behaviors when released.[177]

Select proposed interventions may be efficacious but are not presently legally viable. SIFs save lives, but their domestic operation is subject to federal prosecution via the DOJ or the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).[178] Opening free-standing SIFs and later expanding their operations to include select emergency rooms across the United States could significantly reduce opioid-related mortality. Other approaches, discussed below, carry their own legal, political, or fiscal repercussions, but also present real opportunities to dramatically slow or reverse opioid-related morbidity and mortality.

In many emergencies caused by infectious or chronic conditions, terrorism, environmental hazards, or natural disasters, public health interventions are either freely distributed or incentivized. For example, communities are provided no-cost vaccinations. Guns are bought back by law enforcement authorities. These emergency victims are compensated for their losses. These handouts and incentives are provided in emergencies for a simple reason: they work to improve the public’s health. Similar approaches may be taken in response to the opioid epidemic.

Public and private sector entities crafting pathways to charge and pay for expensive OUD treatments and rehabilitation services should look as well to creating incentives for persons to engage in preventive measures. Patients with temporary pain who opt out of opioid prescriptions should get a rebate from their health insurer. Excess prescription opioid collection drives could include cash buybacks or distributions of gift cards. Opioid abusers should be offered direct financial benefits (or at least free options) to undertake approved treatments. Prisoners undergoing treatment while incarcerated may garner their own benefits in the warden’s discretion. Coupled with each of these incentives are effective risk communications centered on targeted public health messaging about the risks of opioid use in any form. To the extent these initiatives intercede to prevent persons from becoming addicted to or dying from opioids, they more than sustain their costs.

Mitigating response efforts must increasingly focus on underage opioid use. Prescription and illicit opioid misuse are highly prevalent in young adolescents.[179] Adolescent opioid prescribing rates almost doubled from 1994–2007.[180] In 2015, an estimated 122,000 minors (ages twelve to seventeen) were addicted to prescription pain relievers.[181] Overdose death rates for minors (ages fifteen to nineteen) more than nearly tripled from 1999–2007.[182] After a slight decline until 2014, rates increased again in 2015 when opioids were at the source of more than half of adolescent drug overdose deaths.[183] For every adolescent prescription opioid overdose, there were 119 emergency room visits and twenty-two treatment admissions.[184]

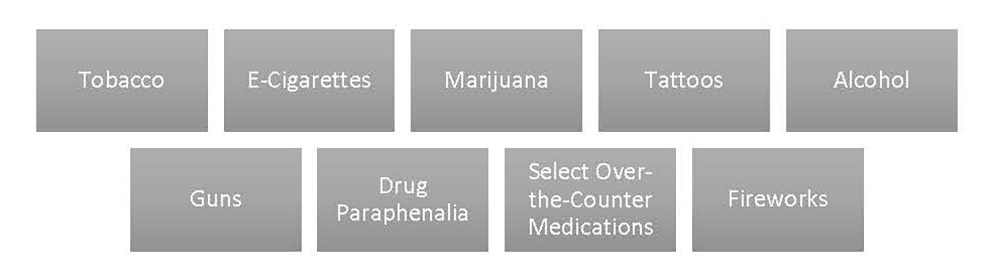

Just like other legal restrictions governing minors’ access or use of multiple products (see Figure 6), stringent opioid prescription limits could decrease opioid misuse and overdose death rates among these vulnerable persons. Persons under age seventeen should be prohibited from receiving an opioid prescription subject to narrow exceptions involving minors with painful, terminal conditions or long-term, irreversible pain. For excepted patients, greater access to preventive measures (including treatment or recovery plans) is essential.

Figure 6. Legal Product Restrictions Concerning Minors[185]

Current legal trends limiting the potency and dosage of opioid prescriptions are promising, but patients are still gaining access to far too many pills nationally. Access to a steady stream of opioids puts patients on the fast-track to addiction.[186] Greater limits on the dispensing of opioids can save lives. Like persons who must pass an examination before receiving a driver’s license, patients should be required to complete risk aversion educational training and testing prior to receiving an opioid prescription.

Those with acute pain (e.g., post-surgery recovery patients) may be treated responsibly with opioids in health care settings. Outside closely monitored settings, patients with chronic or significant pain should be allowed access to opioids only where alternative palliative care or other methods (e.g., OTC drugs, physical therapy) are proven ineffective. Significant investments in opioid prevention research would help identify instances where less risky alternatives to opioids for palliative care were as or more effective.

Tamping down opioid prescriptions is a two-way street.[187] Providers authorized to prescribe opioids should also be required to complete MAT training as a condition to obtaining and renewing licensure. Increased knowledge and testing among patients and providers contribute to more informed decision making about pain management. Requiring non-opioid pain management alternatives prior to opioid prescriptions may diminish rates of opioid misuse.

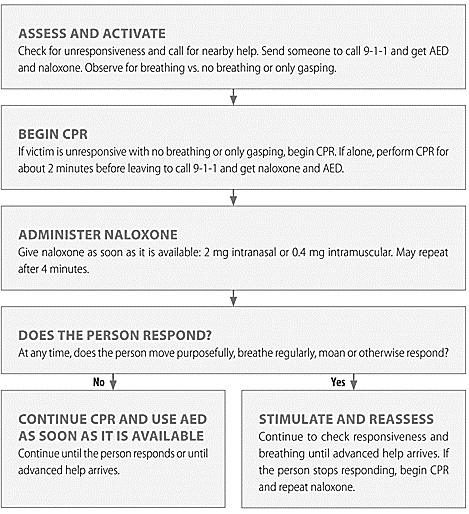

Despite arguments for making naloxone available over the counter (OTC) to at risk persons or caretakers, widespread access remains inhibited for illegitimate reasons. Naloxone is not a controlled substance, has little to no side effects,[188] and has no significant abuse potential.[189] Although forty-five states have issued standing orders allowing wider distribution of the drug,[190] access remains problematic due to a lack of consumer awareness[191] and prohibitive naloxone pricing.[192] The FDA is considering whether to (1) mandate co-prescribing naloxone with opioid prescriptions and (2) allow naloxone to be sold OTC.[193] These initiatives will cut overdose fatalities by proactively placing naloxone with people who can rapidly administer it.

Strategic public placement of naloxone is also essential. Multiple lawmakers support adding opioid antidotes to automated external defibrillator (AED) cabinets.[194] The University of Rochester already includes naloxone in its cabinets.[195] VA hospitals nationally are preparing to follow suit.[196] Given its availability in nasal mist form (i.e., Narcan®), even bystanders can follow basic instructions on naloxone administration (see Figure 7). National commitments to assisting persons at risk of death or serious morbidity due to opioids can improve survivability of victims so long as naloxone is available in places people can readily identify.

Figure 7. Opioid-Related Emergency Instructions[197]

Fighting a multi-dimensional epidemic is not easy when data about its reach and impacts are largely retrospective. Current public health surveillance methods concentrate on prescription drug monitoring and overdoses reported in emergency departments or by paramedics.[198] Existing data are purposeful but also under-funded, incomplete, and insufficient in determining specific emerging risks among affected populations.

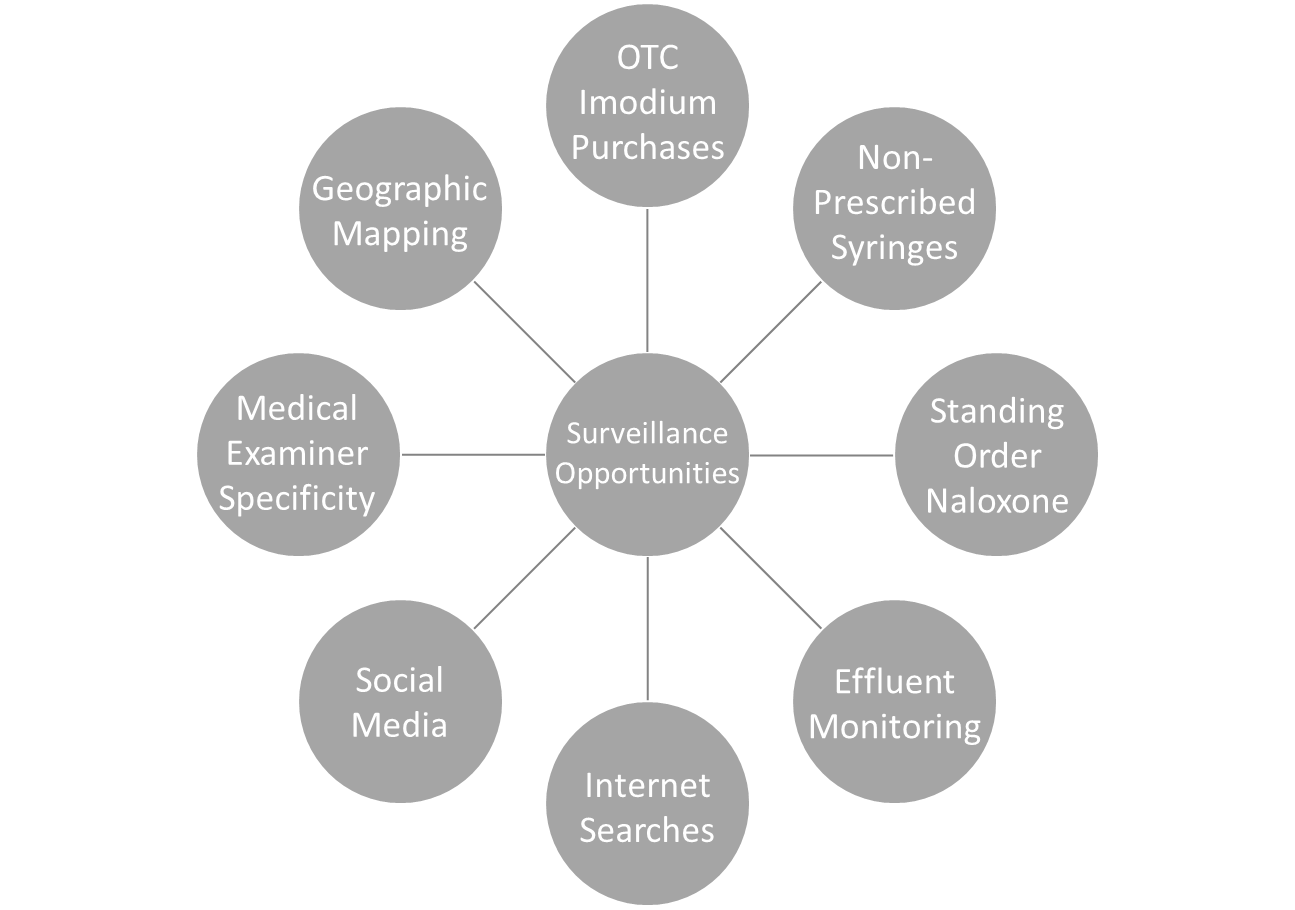

As the crisis shifts, so must commitments to generating and responding to accurate, timely data sources. Renewed investments and data (see Figure 8) may identify high-risk communities, improve treatment and other resource allocations, and assess the effectiveness of innovative responses.[199]

Figure 8. Enhanced Data Methods and Surveillance Tools

Encouraging medical examiners to better specify what kind of opioid precipitated a fatality may illuminate the impacts of prescription versus illicit opioids.[200] Conducting syndromic surveillance on anonymous purchases of the OTC medication loperamide (Imodium®) may reveal sub-populations attempting to mitigate opioid withdrawal symptoms.[201] Close monitoring of purchases of prescribed naloxone and non-prescribed sterile syringes enhances community risk assessments.[202] To support community public health surveillance, the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University monitors geo-localized levels of pharmaceutical and illicit drug consumption by analyzing metabolites in wastewater.[203] Untapped data streams, including internet search history and social media posts, offer new surveillance techniques,[204] notwithstanding privacy repercussions.

Uniform data reporting through existing and emerging sources nationally may obviate impacts of the epidemic through better informed responses. Methods that leverage data to map local jurisdictions can highlight high-risk areas and enable targeted interventions.[205] New developments enable better distribution of naloxone to communities in need through analysis of the locations of overdose events against pharmacies carrying naloxone.[206] Access to enhanced and new data—combined with support and incentives for state and local public health officials—will bolster responses and adaptability to the opioid crisis.

The opioid epidemic began with the notion that patients deserved greater access to palliative care. Decades later, the known consequences of America’s worst PHE are appalling. Hundreds of thousands are dead prematurely due to opioid addiction escalating to overdose. Millions are at heightened risk. Tens of thousands of youth are exposed to these drugs in prescription and illicit forms. Responding to lingering emergencies at this level requires prevention innovations. Efforts focused on (1) substantial incentives to engage at-risk persons, (2) minors’ limited access to opioids, (3) restrictions on secondary prescriptions, (4) strategic placement of naloxone, and (5) advanced surveillance techniques represent more than cost-saving investments in the public’s health: they could be life savers for thousands of Americans facing a scourge they cannot defeat alone.